In what is now Italy, but what in the 14th and 15th centuries was a fragmented network of rival and restless city-states, enterprising soldiers of fortune found themselves in a sellers' market. These mercenary leaders of men, the condotierri ('contractors'), hired out their military services either to Milan or to Florence or to other city-states, and were not shy about changing their allegiance from one city-state to the other, and even back again, as the expediencies of the moment dictated. Then, as now, whatever the language used by these mercenary captains, and whatever their countries of origin, what talked the most eloquently was money.

Two such condotierri were the Italian Bartolomeo Colleoni and the Englishman Sir John Hawkwood, commander of the notorious White Company. Although a century divided these two men from each other in time, they led similar and somewhat parallel careers, swapping sides a number of times with ready alacrity. But apparently there was a difference in temperament between the two.

Where Colleoni seems to have been moderate and even-tempered, Hawkwood was ruthless and morally ambivalent. Where a trail of sound strategy and successful campaigns might lead you to Bartolomeo Colleoni, a trail of sound strategy, successful campaigns and civilian corpses would as likely lead you to Sir John (there is no clear historical record of Hawkwood formally receiving the order of knighthood, and the 'Sir' could have been a self-assumed title designed to increase his prestige and bankability).

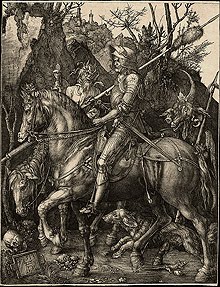

Art has left us two likenesses of these captains of expediency. Bartolomeo Colleoni was foresighted and practical enough to bequeath a sum towards the erection of an equestrian statue in honor of himself (below). The work was sculpted by Andrea del Verrocchio, cast in bronze, and erected in the square in front of the Church of Saint John and Saint Paul in Venice. But the realization of Hawkwood's monument, as with his dubious altruism, was more problematical. Some four decades after his death, and another four decades before Colleoni's death prompted the creation of his own bronze likeness, the grateful Republic of Florence, overlooking the fact that Hawkwood had on more than one occasion in the past actually fought against the Republic, decided to honor John Hawkwood with his own equestrian statue.

But it was decided that the commission should be, not an actual bronze statue, but a painting of a statue (above). What could have prompted such a curious compromise? Perhap it was the artistic limitations of the time, for another few decades would pass before such artists as Verrocchio and Donatello would successfully revive the creation of such grand sculptural works; the first of such statues since Roman times. Perhaps it was the compromising forces of financial expediency, for the production of such bronze works would have been as epic in their cost as they were in their scale. Whatever the reasons, this painted, two-dimensional statue would be commissioned from the artist Paolo Uccello, and executed in fresco on the wall of Florence Cathedral.

A comparison of these two works of art is both revealing and puzzling. For it is Verrocchio's bronze of Colleoni that positively bristles with vigor and agressive energy. As portrayed by Verrocchio, Colleoni's hatchet features glare down at us from his steed with haughty and imperious disdain. In contrast, Uccello's Hawkwood, who in life appears to have been the embodiment of the way in which Verrocchio portrayed Colleoni, seems to sit astride his mount with all the amiable contentment of a public official riding in a parade.

How could this be? Even given that this fresco is the earliest work that we can attribute to the artist, this is, after all, the work of Paolo Uccello. Uccello, whose ground-breaking use of perspective gives such you-are-there flair and writhing action to his monumental 'Battle of San Romano', which he was to paint a few years later, and which was to catch the attention of no less a personage than Lorenzo de Medici.

Opinions differ as to whether the reasons were to do with the seething politics of the age, or whether there were any grounds for objection based upon the artistic conventions of the time. Whatever the reasons, the fact remains that upon completion of the work Uccello was asked to entirely repaint both horse and rider. Ultraviolet analysis, together with an existing sketch, reveal that Uccello's original Hawkwood was altogether more Hawkwoodish. This first, invisible Hawkwood is in full armour, with baton commandingly raised and charger ready for the fray.

A pity indeed that Hawkwood's monument was not realised in the form of a Colleoni-style bronze statue, rather than as a mere painted version of one. Bronze denies the ready amendments possible with a layer of paint. And Uccello's knight of dark renown would more likely have expressed exactly those ruthlessly commanding Hawkwood qualities of character had it not been compromised by alteration.

Artist: Paolo Uccello

Work: Monument to Sir John Hawkwood, 1436

Medium: Fresco

Location: Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

Sources:

'John Hawkwood: An English Mercenary in Fourteenth Century Italy'

by William Caferro. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

'A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century'

by Barbara W. Tuchman. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1978.

Two such condotierri were the Italian Bartolomeo Colleoni and the Englishman Sir John Hawkwood, commander of the notorious White Company. Although a century divided these two men from each other in time, they led similar and somewhat parallel careers, swapping sides a number of times with ready alacrity. But apparently there was a difference in temperament between the two.

Where Colleoni seems to have been moderate and even-tempered, Hawkwood was ruthless and morally ambivalent. Where a trail of sound strategy and successful campaigns might lead you to Bartolomeo Colleoni, a trail of sound strategy, successful campaigns and civilian corpses would as likely lead you to Sir John (there is no clear historical record of Hawkwood formally receiving the order of knighthood, and the 'Sir' could have been a self-assumed title designed to increase his prestige and bankability).

Art has left us two likenesses of these captains of expediency. Bartolomeo Colleoni was foresighted and practical enough to bequeath a sum towards the erection of an equestrian statue in honor of himself (below). The work was sculpted by Andrea del Verrocchio, cast in bronze, and erected in the square in front of the Church of Saint John and Saint Paul in Venice. But the realization of Hawkwood's monument, as with his dubious altruism, was more problematical. Some four decades after his death, and another four decades before Colleoni's death prompted the creation of his own bronze likeness, the grateful Republic of Florence, overlooking the fact that Hawkwood had on more than one occasion in the past actually fought against the Republic, decided to honor John Hawkwood with his own equestrian statue.

But it was decided that the commission should be, not an actual bronze statue, but a painting of a statue (above). What could have prompted such a curious compromise? Perhap it was the artistic limitations of the time, for another few decades would pass before such artists as Verrocchio and Donatello would successfully revive the creation of such grand sculptural works; the first of such statues since Roman times. Perhaps it was the compromising forces of financial expediency, for the production of such bronze works would have been as epic in their cost as they were in their scale. Whatever the reasons, this painted, two-dimensional statue would be commissioned from the artist Paolo Uccello, and executed in fresco on the wall of Florence Cathedral.

A comparison of these two works of art is both revealing and puzzling. For it is Verrocchio's bronze of Colleoni that positively bristles with vigor and agressive energy. As portrayed by Verrocchio, Colleoni's hatchet features glare down at us from his steed with haughty and imperious disdain. In contrast, Uccello's Hawkwood, who in life appears to have been the embodiment of the way in which Verrocchio portrayed Colleoni, seems to sit astride his mount with all the amiable contentment of a public official riding in a parade.

How could this be? Even given that this fresco is the earliest work that we can attribute to the artist, this is, after all, the work of Paolo Uccello. Uccello, whose ground-breaking use of perspective gives such you-are-there flair and writhing action to his monumental 'Battle of San Romano', which he was to paint a few years later, and which was to catch the attention of no less a personage than Lorenzo de Medici.

Opinions differ as to whether the reasons were to do with the seething politics of the age, or whether there were any grounds for objection based upon the artistic conventions of the time. Whatever the reasons, the fact remains that upon completion of the work Uccello was asked to entirely repaint both horse and rider. Ultraviolet analysis, together with an existing sketch, reveal that Uccello's original Hawkwood was altogether more Hawkwoodish. This first, invisible Hawkwood is in full armour, with baton commandingly raised and charger ready for the fray.

A pity indeed that Hawkwood's monument was not realised in the form of a Colleoni-style bronze statue, rather than as a mere painted version of one. Bronze denies the ready amendments possible with a layer of paint. And Uccello's knight of dark renown would more likely have expressed exactly those ruthlessly commanding Hawkwood qualities of character had it not been compromised by alteration.

Artist: Paolo Uccello

Work: Monument to Sir John Hawkwood, 1436

Medium: Fresco

Location: Basilica di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

Sources:

'John Hawkwood: An English Mercenary in Fourteenth Century Italy'

by William Caferro. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

'A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century'

by Barbara W. Tuchman. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1978.

No comments:

Post a Comment

You are welcome to share your thoughts..